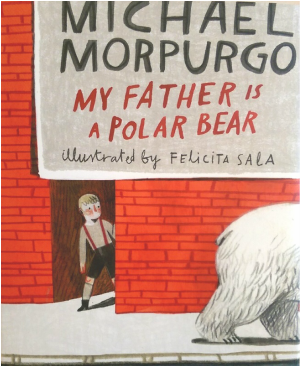

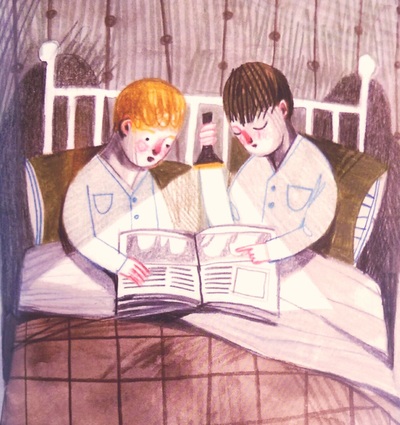

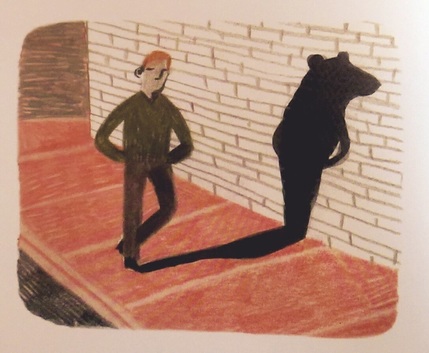

Felicita Sala's rich, textured illustrations bring the story to life Felicita Sala's rich, textured illustrations bring the story to life Every so often, a real gem comes along and tugs on my heartstrings. Michael Morpurgo's My Father is a Polar Bear is one of them. Newly released in picture book format by Walker Books, with illustrations by Felicita Sala, this captivating story was originally published in a collection of short stories, From Hereabout Hill, in 2000. A masterful storyteller, Morpurgo skillfully draws from his own childhood experience in his telling the story of two little boys, Andrew and Terry, as they attempt to find their biological father. From the very first line 'Tracking down a polar bear shouldn't be that difficult', we are acutely aware that we are inside the head of a young child in pursuit of an elusive father figure. Admirably, Morpurgo doesn't tiptoe around this as we so often find with 'sensitive' issues in children's books. He very deliberately dives in head-first. Two pages in, he gives us the story of the boys' parents' relationship, from the point of view of Andrew looking back from his adulthood, 'Some background might be useful here. I was born, I later found out...'. His use of the first person, past-tense narrative, allows us to dive in to memories from Andrew's childhood in real-time but to also appreciate that we are looking back from some future point. Andrew tells us how his 'real' father is never talked about by his mother or step-father. All they know is that they were given his name; Van Diemen. Andrew and Terry are forced to discuss him in the secret hours of the night. On one such occasion, Terry produces a magazine with a photo from a theatre production of 'The Snow Queen', on one of it's spreads. A polar bear poised with arms reaching out sprawls over the pages; the caption below revealing the actor under the suit to be none other than their missing father, Peter Van Diemen. Throughout the story, their father is referred to by them as 'the polar bear father', reflecting the impact of this first discovery. It's the use of time in this story that I found to be particularly affecting. Time, as we know, slips from our fingers all too readily. The story starts in 1948, with references to shillings and the second world war, when Andrew is 5 years old. It's at this stage that Morpurgo reveals the approach the family takes to the boys father: 'My first father, my real father, my missing father, became a taboo-person, a big hush-hush taboo person that no one ever mentioned, except for Terry and Me.' The years roll on and we see a brief glimpse of the boys father on the television some fourteen years later- to which his mother shouts out in surprise, confirming his identity. The boys approach her for more information soon after, but her reluctance to entertain her past is too powerful, as is so often the case when we want to move on. We can all too easily forget the consequences for those around us, as this story powerfully conveys. Morpurgo expresses the deep-felt sense of a partial identity, with true craft, in the closing pages. The boys, now adults with their own families, finally go to see their father. 'There was a lot of hugging in the dressing room that night, not enough to make up for all those missing years, maybe. But it was a start'. The very idea that there can be a start so much closer to the end is highly telling. This was always the beginning for the boys - the beginning of their history - and their identity. Morpurgo's own feelings are perfectly executed by his words: 'It's history best crusted over, I think.' The use of the word 'crusted' alone provokes a sense of a weeping wound, though an old one that's now healing. He points out that Andrew's grandchildren refer to their grandpa as 'Grandpa Bear' because 'they all know the story of their Grandpa, I suppose.' In the closing pages Andrew playfully tells us that he recently wrote a story about a polar bear, 'I can't imagine why'. These closing remarks resonate how important his father was to him, throughout his life. This exquisite feat of storytelling completely transports us into the world of Andrew and Terry, and that of Morpurgo as an adopted child. It captures perfectly the lingering sense of loss, missing identity and isolation that an adopted child can feel. Some children don't want to know or need to know about their biological parents: my own father was adopted and for him, his story firmly lies with his adopted, or 'real' parents as he sees it. That was his choice, and one which was his from a very young age. Morpurgo's story does not dictate to the reader how to deal with adoption or single-parenthood; it simply seeks to share an experience. As the best stories do.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

More posts coming soon...

Archives

July 2016

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed